Georges Baines (BE)

In collaboration with:

Architectenunie (O.Vl.)

(autotranslated)

There is no doubt that the architecture as the active component in bringing about a better society in Belgium has ended in utter failure. The causes for this state one should look for in the period immediately after the war, when some of the best architects of a generation not reached maturity succeeded in achieving what might have been expected of them. For all of us it lacked a catalyst, a master who could lead us to think, like Smithson in England or Bakema in the Netherlands. Van de Velde was old and stayed abroad, the work of the De Koninck was modest (below modesty reasonable one: a judicious restraint in thought and action) and it too personal work Braem contributed not the ferments the young people new ways had to focus. Since there was no fruitful contact with the elderly and no serious take group aanstuurde there to exchange ideas (National CIA was delusional and one Belgian later made part of Team X). each of us withdrew into his own world. While in other countries led the architectural competitions to fruitful competition and to discover new talent, was granted simply with us most of the contracts based on political docility.

The balance of these thirty years is for me so negative, despite all attempts and sometimes satisfactory results, limited as they were not able to give our architecture proved its own character or an international value. However, it would not be fair to limit themselves to this pessimism, because just the last few years, one can recognize the premises of a renewal. If on the one hand, on the part of the administration and teaching the future remains bleak, one notices while staying some promising elements: the constructive attitude of the younger honor, the revival of an architectural criticism and finally the realization of the main subject, the audience.

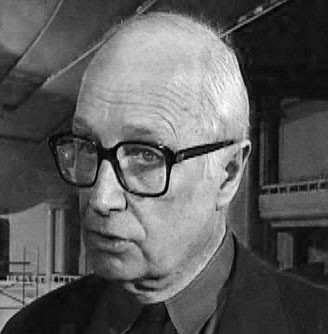

Georges Baines

born in Antwerp on May 7, 1925.

Architecture Studies at the National Institute of Architecture and Urbanism in Antwerp, diploma in 1950. CIAM summer school in Venice in 1952. Works independently since 1957. Member of the editorial board of the journal A. From 19? until 1961. Member of the editorial board of the journal LM. / E. Since 1968.

Awards: 1965 National Architecture Award from the National Wood Information Office, special mention of the jury. 1965 national architecture award from the National Wood Information Office, first prize. 1968 first prize in the Van de Ven competition. Since 1965, teacher-lecturer in architecture at the National Higher Institute of Architecture and Urbanism in Antwerp.

Below are some extracts from the magazine AMA 1980 BAINES which we made available.

DWELLING SCHELLE, 1976.

The house in Schelle, conducted in 1976, was conceived in order to favor dialogue between nature and some places of the house. A kind of green living room, enclosed by a hedge beech 2m high, above the entrance overhung by a canopy. The construction is built around an old weeping willow, the last vestige of an ancient garden. From the entrance hall, it appears as the focal point of all eyes, the rallying point of all practices. It overlooks a fully glazed space that takes the full height of the house and on which fan out the different pieces that make up the. On the ground floor, it separates the living room, bounded to the ground by a floor, a noisy area: kitchen and dining room in visual contact with the bread oven. Between the oven and the garage, a work table is provided for the preparation of preserves, as well as a shower. Upstairs, the central space is bordered by a bridge between the part intended for children sharing parents room. The autonomy of these two entities is pushed to the concept of “house within a house” that will find its culmination in the house Braunschweig. Thus, the area of children and the parents are each defined by an inner façade day taking on the central space; In the same way, the bread oven opens a discrete window on the kitchen.

SCHOOL PROJECT A FROEBEL BORGERHOUT, 1978.

Initially modular research and reflection on the “units” conducted by Van Eyck and his school, Georges Baines tries to distance himself from some functionalist concepts of contemporary architecture. The Froebel School, for example, is composed of a set of units that do not maintain them no relation of subordination: each unit is a separate entity, it enjoys both a certain degree of versatility and autonomy. Thus, the four classes appear both in plan and volume and facade, like so many houses appropriated easily by children. The design of doors and windows is the expression of a familiar architecture; similarly, the small gardens at the rear of classes recall the suburban garden. The main building houses the services and areas for joint activities. With the vast full games preceding it, it reflects a more urban report, the move to a neighborhood scale. The project has been designed taking into account the State’s regulations. It is located in one of the most popular neighborhoods of Antwerp.

THE PAVILION FLANDRIA, 1976.

Flandria pavilion, planned to replace the current building had become too small, was studied – because of the exceptional situation on the Steenplein – to accommodate the service of Flandria company that organizes boat trips, as well as the information service tourism of the City of Antwerp. It has been designed to minimize interference with the view that one has on the Scheldt from the main square (Groenplein).

This is what has driven the party to build on 2 levels – the second level disappearing into the tops of the existing trees. The kiosk refers, by its appearance, Traditional kiosks; but also suggests maritime architecture (use of metal frames painted gray, portholes). Constructive party relies on the use of different structures independent of each other: a mushroom supports the slab of the first floor which is balanced in part by the outside staircase. Because inflections that will undergo the slab, the steel structure supporting the glass roof which runs along the adjoining building by means of hinges; full autonomy is ensured him.

On the ground floor, a series of screens determines the distribution of different premises.

HOUSE BRAUNSCHWEIG, 1976.

Braunschweig The house is located in a fairly nondescript these new periphery neighborhoods of Antwerp. The avenue is without urbanistic feature except the obligation to provide a garden in front. This construction, however, is the first Georges Baines confronting the issues raised by the house between party walls; and this constraint is originally part of the complexity surrounding its plane.

Braunschweig somehow symbolizes the culmination of what we might call the first architecturally Georges Baines, it expresses the shift to a mode of expression that reintegrates the nostalgia of a certain quality of etiquette. This desire to rehabilitate the forgotten practice of everyday life brings Baines to work particularly the transitions between different places, solve both through color and light, as the complex geometry of internal spaces.

To access the house, you have to cross what should have been a decorative garden, and Georges Baines treated as a small paved courtyard which extends quite naturally the sidewalk and can accommodate the children’s games. It is limited by a low wall which stops to turn into bench: perhaps someone he sit there in the shade of the tree.

The house itself does not take all the depth allowed by the plot; and to prevent the rear facade, facing south, is taken between the party walls blinders, Baines has opted to leave the three levels of the house like the drawers of a cabinet: the garden side, the sun penetrates deep in the conservatory and the stay; street side, against the graduated-form by the two levels overlooking the reception and suggests that porch office. The two columns that support the first floor frame the entrance partially hidden by the wall that supports the second. When you override this wall which is leaned a semicircular bench, we see, over through the entrance hall and beyond the hall, part of the garden.

The lock looks like a glass cage standing out from the front of the ground floor: it is not really inside the house. One enters obliquely; then, along the mid-height wall that hides the stairs from the basement to look, we arrive in a space flooded with light: left, a curved wall features the hand basin and cloakroom. Color, it softens the rigor of the axial composition; right, as a prelude to the nearby garden, the conservatory opens onto a huge window over the height of construction.

The spiral staircase leads upstairs is treated as outside the building. It completely frees the space of the plot and accentuates the imaginary central plane which divides the house into two distinct parts: an intimate and relatively closed in on itself (the kitchen and a covered terrace, dining room sheltered by stairs); the other wide open, turned to the veranda and garden.

At first glance, it is tempting to resemble such a type of organization of space to the rules of classical composition. However, various factors contradict that impression: the views are not geared in a preferred axis, but are instead multiplied in various directions in the vairées directions. Thus, the dining room, for example, it is possible to see through the bay window, the park located in the center of the street perpendicular to the house; by cons, from the small window illuminating the space provided at the back of the stairs, the look along the parallel ru. Towards the living room, the view through the conservatory and dive into the garden through the bay window; and beyond the kitchen, through the glass door, we guess the terrace and garden.

Some rooms open by true interior facades on the veranda. They entail complex relationships in the home and in-sparing views through intermediate closed spaces. From the kitchen, for example, look through the terrace and from the window of the bridge, he entered the conservatory to get lost finally in the garden. Similarly, rooms at second level take on the veranda day-to through which the garden is looming.

A column is the pivot around which organizes the entire composition of the space of the first two levels: in the manner of a Brancusi sculpture, it suggests movement and accentuates the spatial link claimed by the volume of the veranda.

The light from white to dark gray (the porch is covered by a stained glass panel inclined at 45 °) and shadow games drawn on the side wall by the frame and walkways that line the transform the veranda e a gigantic moving abstraction.

These elements, combined with the use of color for some non-structural elements of the building, allow to consider the hypothesis of an imperceptible shift towards a mode of expression within the baroque complexity.

GROUP STUDY OF 6 UNITS Residental 1978.

This research is the culmination of the house Braunschweig. It concerns the possible grouping of several homes of the same type, divided into apartments. The main constraint is retained by Baines development of direct access to the gardens from the street and the different staircases.

If they are arranged in two distinct areas separated by a walk: the first is for individual gardens accessible from the apartments on the ground floor; the second is for occupants of apartments located upstairs.

The diagonal passes allow access to group; they are treated in the way of fully glazed bisector planes taking day facade and roof. The plans of the apartments are arranged so as to respect the best that party.