Francesca Torzo (IT)

Francesca Torzo is in 2019 holder of the Chair Maarten Van Severen. Since 2015, KASK and the Maarten Van Severen Foundation have been inviting an authority from the design world every year. During a public lecture in March and a workshop for students, they place Van Severen’s legacy in a modern light. Francesca Torzo (1975) is an Italian architect-maker, an architect who makes architecture in a sensitive way. She studied architecture in Delft, Barcelona, Mendrisio and Venice [IUAV]. She worked for architect Peter Zumthor and Bosshard Vaquerarchitekten, Zurich. In 2008 she started her own architectural practice in Genoa. She drew, among other things, the recent expansion and renovation of Z33 in Hasselt.

Francesca Torzo is in 2019 holder of the Chair Maarten Van Severen. Since 2015, KASK and the Maarten Van Severen Foundation have been inviting an authority from the design world every year. During a public lecture in March and a workshop for students, they place Van Severen’s legacy in a modern light. Francesca Torzo (1975) is an Italian architect-maker, an architect who makes architecture in a sensitive way. She studied architecture in Delft, Barcelona, Mendrisio and Venice [IUAV]. She worked for architect Peter Zumthor and Bosshard Vaquerarchitekten, Zurich. In 2008 she started her own architectural practice in Genoa. She drew, among other things, the recent expansion and renovation of Z33 in Hasselt.

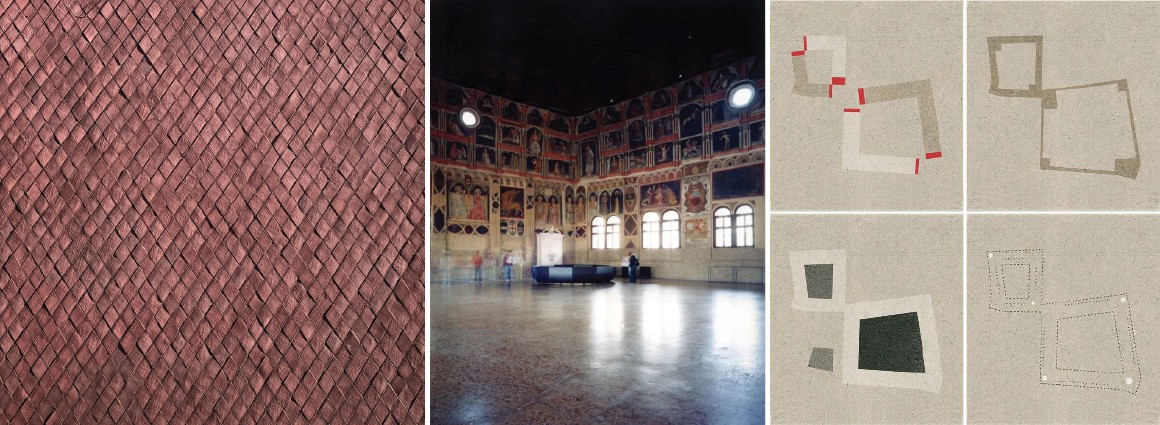

Francesca will talk about the wishes, the memories and the promises of experiences that we enliven, where the threshold of the individual merges into a collective knowledge. Culture is a paradoxical phenomenon: it is a collective living being that is formulated and challenged by the actions and thoughts of individual people, those who live and those of ages and millennia ago. In order to have the present reflect both the past and the future, and thus contribute to a collective culture, there is a need for asking questions and observing what we already know beyond the form. Objects, buildings and cities express the slow phenomena of human culture, that un-ravels in time far beyond the life of an individual being, thus the question underlying our work is how to instru-ment them in a way that they can resound truthfully to people, rousing memories of what already exists and kindling visions of something which does not exist yet.

The hypothesis at the base of this search is that rela-tions among spaces and human gestures have a specificity that allows to awaken memories of other spaces and gestures, beyond form and beyond material. In our practice the process of design starts from an under-standing of the material constrains and of the cultural context where we are called to operate, through a disci-pline of observation and reflection. The goal is that of formulating the primary relations, which have to be pre-served through the complete process, from design to detailing and execution phase, in order to do not deceive an expectation of experience. The recognition of these relations that allow us to access experiences lived by us or others, to remember them and to imagine new ones building a dialogue with other times, is the instrument of our cultural expression, unique for each individual and occasion.

Antoine Lebot

Antoine Lebot

The architect’s profession is complex; so is the one of a designer. We have to negotiate and interpret material constrains such as budget, building regulations, programs of use, available technologies, and we have as well to understand and interpret culture, desires and memories of people that most of the time we do not know in person, in the case of private as well as public assignments.

Interpreting our profession as a patient practice of observation of these material and cultural phenomena, which we believe we have the responsibility to coordinate in the construction of a building, has the goal of orchestrating spaces and objects for every day gestures able to offer an authentic experience to people, establishing a dialogue, not necessarily in continuity, among the cultures that preceded us and the ones to come.

Objects, buildings and cities express the slow phenomena of human culture, that unravels in time far beyond the life of an individual being, thus the question underlying our work is how to instrument spaces in a way that they can resound truthfully to people, rousing memories of what already exists and kindling visions of something which does not exist yet.

Reflecting on architect’s profession, we recognize a paradox in the coexistence of a common understanding of spaces and in an individual specificity of the same understanding, different for each of us.

We have the ability to recognize and to name spaces, such as a room a terrace a tower so that we can communicate with others in our daily life, but most of the times each of us will have its own experience of a room a terrace a tower, recalling a memory of a visit or of a reading or even of a scene from a movie.

The main point of interest of our research lays in this paradox, since we observe that when we stand in a space surprisingly memories of other spaces arise and that often these memories belong to space, which may differ from a parametric or common definition of it. We may have visited a house experiencing it as a walk through a portico, even if that house is not a covered ambulatory; our mind is able to make unpredictable interlacements and therefore we may live and share with others the experience of a portico in a sequencing of rooms.

Similarly, while sitting on a bench or holding a spoon, we may recall our past experiences or the ones of others.

The hypothesis at the base of this search is that relations among spaces and human gestures have a specificity that allows to awaken memories of other spaces and gestures, beyond form and beyond material.

In our practice the process of design starts from an understanding of the material constrains and of the cultural context where we are called to operate, through a discipline of observation and reflection. The goal is that of formulating the primary relations, which have to be preserved through the complete process, from design to detailing and execution phase, in order to do not deceive an expectation of experience.

If the primary relations are clear, even adaptations of materializations and details may be non-influential as long as they do respect the narrative.

The recognition of these relations that allow us to access experiences lived by us or others, to remember them and to imagine new ones building a dialogue with other times, is the instrument of our cultural expression, unique for each individual and occasion.

There is no preconceived language, not in the process nor in the result.

Material, language and design tools are defined by the research, which is specific to each assignment and to the communication of the story in relation to the interlocutors, in search of the meeting point between the individual perception and the collective understanding.

This approach has similarities to the scientific method, where an experiment is developed continuously sifting individual perceptions and objective observations.

Francesca Torzo