Bruges modernism: a case on the fringe?

Matthias Decleer

Matthias Decleer

Archipel on the move, on foot or by bike, to discover architectural gems in Flemish cities. On the road together!

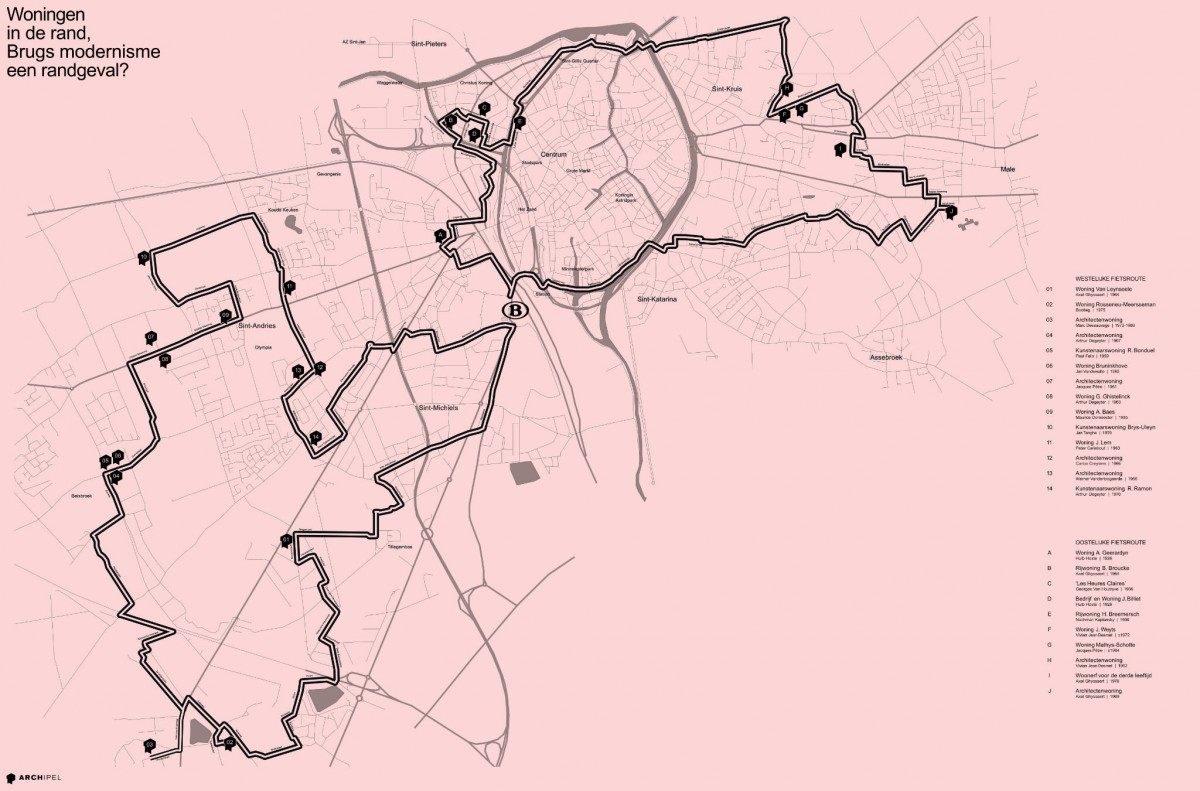

Taking into account the COVID-19 situation, in 2021 we will be focusing on a number of outdoor activities such as bicycle tours and/or city walks. Archipel makes a number of thematic architecture maps to discover the city by bicycle or on foot. The route along modernist houses in the outskirts of Bruges is also a call for protection of modernist buildings.

Until 1970, conservative and bourgeois Bruges was not much bigger than the medieval ramparts. Here, the Stedenschoon Committee watched over “what fits” and especially over “what doesn’t fit”. The creed of the Pugian Gothic Revival was applied literally and figuratively as if it were the catechism. City expansions were scarce and, like the Kristus-Koningwijk, were also conceived with strict regulations that left no room for any modernity. Very exceptionally, an architect was able to escape the vigilance of the committee, such as the art-deco house Les Heures Claires in the Gouden Boomstraat or the extension of a school in the Giststraat.

The young post-war generation fled the compulsion of the city center and also found cheap building plots in the suburbs. Sint-Andries and Sint-Kruis in particular were rewarding destinations, well connected to the city center and situated on an old dune ridge, with good and dry sandy soil to build on. Here a new generation of architects – all starting their careers in the period of Expo ’58 – could live up to their ideals. The enthusiasm was limitless, so was the economic growth and no one had the slightest doubt about a better future. The influence of the American way of life and its architecture is undeniable. In the early 1970s things got more serious, have times changed? The Ramon, Degeyter, Dessauvage and Weyts residences look tougher with a more closed volume game.

Before them, a few Bruges architects had paved the way to the peripheral municipalities: Huib Hoste as well as the lesser known Maurice De Meester had become acquainted with Dutch modernism during WWI and brought them to Bruges. Here, too, the peripheral municipalities and the edge of the city center were found to be good enough to include these “peripheral cases”. At the same time, in the city center, until well into the 1970s, there was plenty of building on in neo-gothic, derivatives or just pastiche architecture.

The tide has turned, or does it just seem that way? The modernist homes of a whole generation of exceptionally talented architects and builders are under threat. On the one hand, the land value in the suburbs has increased about tenfold compared to the value of these experimental homes from the 1960s. On the other hand, there is the ghost of the EPB. Good insulation is hard to find in these homes and the glass/outer shell ratio is excessive, not to mention the oversized outer surfaces and thermal bridges. Renovating such homes while meeting energy requirements is an expensive joke and in many cases even impossible. The result is visible: the modernist heritage is being demolished. The work of Jozef Lantsoght that cannot be discussed here has been demolished or mutilated (Structo factory, artist’s residence Rik Slabbinck). Furthermore, for example, the Lefevre house, award-winning design by architect Peter Callebout, has recently been demolished and replaced by what is commonly called a rectory house. The artist’s house Michel Martens on the Zeeweg, work by Arthur Degeyter, was also demolished despite its protection status.

We have put together two cycling tours around a number of prominent examples, which are no coincidence in the outskirts of Bruges. With the intention of telling the unambiguous story possible, we limited ourselves to residential buildings, not apartments, schools or other structures. We also attempted, as far as possible, to investigate the original builders. Time is running out to give these buildings the necessary attention. It is no longer possible for a city, famous for its concern for heritage, to sweep this building history under the carpet. And yes, a lot of good will will be asked of the new owners to cherish this pieces of heritage, but also a lot of courage from the government not to give way to the most easy-going solution: demolition!

Géraldine Vandenabeele

Programme

The cycle tour takes you past 15 modernist houses.

Artist’s home R. Ramon of architect Arthur Degeyter | 1970

Renaat Ramon, poet, essayist and sculptor, commissioned architect Degeyter in 1970 to design a house next to his studio and company. The site has an unfavorable position in terms of sunlight, but this was handily solved by projecting the volume of the garage to the street side, so that the two-storey main volume could be fully oriented to the southwest. The surprise is all the greater when one walks from the dark closedness of the street side into the open living space, where the couple lives amid their books, works of art and furniture designed by the artist.

Van Leynseele house by architect Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

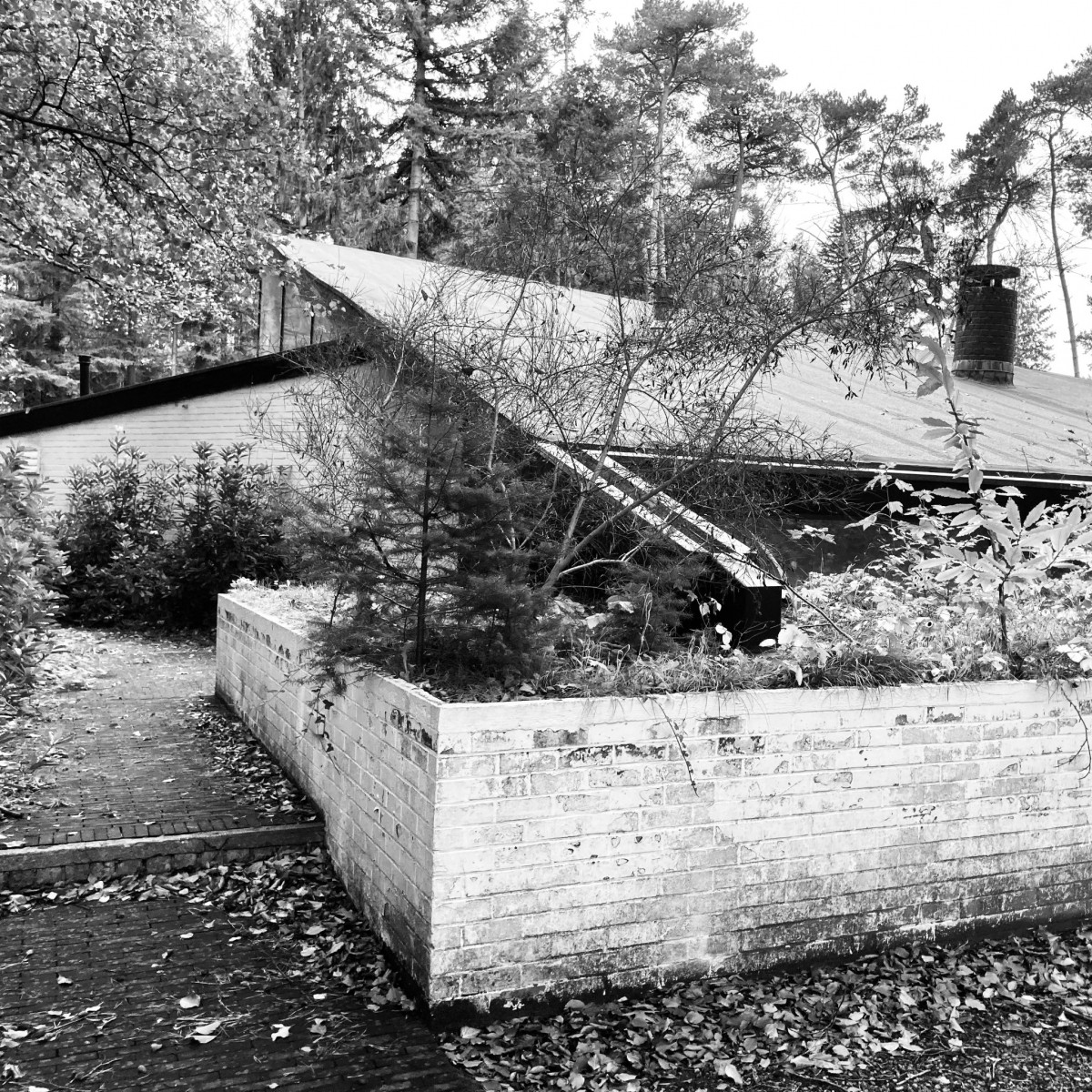

The surprising volume game is nevertheless simple in concept: two wings, in an L-shaped plan with a strict separation between living and sleeping areas, face an open space in the forest, the garden. Both volumes, concealed under a gently sloping roof, seem to float in a playful dialogue above the open walls on the garden side. Towards the public domain, the house is fairly closed because both roofs rise up from the forest floor, as it were. The design is a search for a balance between the intimacy and closeness to the outside world and the openness in the interior, and between the two wings. The young family that moved to Bruges to set up a new factory there approached Ghyssaert as an architect for their home.

Architect house of architect Arthur Degeyter | 1967

In 1965 architect Degeyter (° Bruges 1919 / † Bruges 2004) built a second home for himself. The site is accessible via a long private road, with the building at the very end. The central entrance separates the ground floor: on the right is his studio and on the left a carport and an open staircase to the living area on the first floor with a splendid view of the garden. It was precisely this search for contact with the garden that was the reason to commemorate the very first design. Initially, the carport, workshop and living space were planned on the ground floor and the sleeping areas on the first floor under a 32-meter long pent roof with a fairly large cantilever on the southwest side. Arthur Degeyter was an incredibly prolific architect, talented draftsman and sketcher, but above all an affable figure. He studied at the Sint-Lucas Institute in Ghent, at La Cambre in Brussels and followed an internship with the Bruges architect Viérin. He once won a first mention and the Van de Ven Prize in 1964.

Matthias Decleer

Artist house R. Ramon | Arthur Degeyter | 1970

Matthias Decleer

Artist house R. Ramon | Arthur Degeyter | 1970

Matthias Decleer

House Van Leynseele | Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

Matthias Decleer

House Van Leynseele | Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Arthur Degeyter | 1967

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Arthur Degeyter | 1967

Artist’s home R. Bonduel of architect Paul Felix | 1959

Roger Bonduel (1930–2019), sculptor-metal artist, and Michel Martens (1921–2006), glass artist, together with Arthur Degeyter, formed a small artists’ colony on the Zeeweg in Sint-Andries. Many architects worked with Bonduel. Ultimately, it was architect Paul Felix (° Ostend 1913 / † Ostend 1981) who designed the house and the studio. The L-shaped plan encloses the garden: the modest studio is located on the short street side and the living areas on the long garden side. Above the outer walls of the studio, the ceiling floats and reflects the light zenithically into the enclosed space. The living area, on the other hand, is fully accessible to the garden. The materiality is sober: inside is outside, outside is inside. Only brick and exposed concrete are used everywhere. The interior still contains all the elements designed by Bonduel, but also by Felix and Martens – especially the exposed concrete fireplace clearly shows how great Felix’s admiration for Le Corbusier was. Paul Felix graduated from the University of Leuven in 1937, where he became a lecturer in architecture 15 years later and exerted a great influence on the next generation of engineer-architects.

Bruninkhove house by architect Jan Vandewalle | 1969

This house, built for the Schutyser couple, is at the very back of the deep site. This keeps a free space in the forest open to the southwest of the living areas. A long journey has been made between the building permit application and the realization. Initially kept austere with two white-painted beam-shaped volumes – living and sleeping areas separated by the entrance – the materiality was less rigid: rough brick walls rhythmically separate the open surfaces of windows and doors. Architect Jan Vandewalle (° 1936) graduated from the Sint-Lucas Institute in Ghent and followed an internship in Spain with Pau Ferragut and in Bruges with Jozef Lantsoght (° Bruges 1912 / † Bruges 1988).

G. Ghistelinck house of architect Arthur Degeyter | 1963

The very extensive oeuvre of architect Arthur Degeyter consisted, especially in the 1950s and first half of the 1960s, of classic, historicizing houses, often with dominant roof and chimney volumes. He showed great respect for the work of Sir Edwin Lutyens. In the mid-1960s his designs evolved towards moderate modernism: simple volumes built with traditional materials. A great example of this was the work of Jørn Utzon of the same period. The Ghistelinck villa is a typical example. The large openness that the entrance shows is planned completely off from the living area at the back, far from the noise of traffic. The simplicity of the volume and materiality is timeless.

Matthias Decleer

Artist house R. Bonduel | Paul Felix | 1959

Matthias Decleer

Artist house R. Bonduel | Paul Felix | 1959

Matthias Decleer

House Bruninkhove | Jan Vandewalle | 1969

Matthias Decleer

House Bruninkhove | Jan Vandewalle | 1969

Matthias Decleer

House G. Ghistelinck | Arthur Degeyter | 1963

Matthias Decleer

House G. Ghistelinck | Arthur Degeyter | 1963

Architect house of architect Jacques Pêtre | 1961

The private home and studio of architect Jacques Pêtre (° Bruges 1930 / † Bruges 2007) immediately betrays the influence of both Arne Jacobsen and – and especially – Richard Neutra. The latter in particular appealed to the Flemish post-war architects with its homes that testified to freedom and optimism. This enthusiasm quickly becomes apparent in this spacious home that occupies the entire site. The garage and house are far apart, but are connected to a garden wall that also hides the private garden from view. A little later, the studio was built to the north of the house. Jacques Pêtre graduated from the Sint-Lucas Institute in Ghent and continued his studies at La Cambre in Brussels and in Venice. He followed an internship in Bruges with architect Luc Dugardyn where he was able to work on the plans for the “Outboard Marine” factory, a modernist work that is now completely disfigured. In the early 1960s, he followed Peter Callebout’s call to unite all West Flemish modernist architects. Eventually he became a co-founder of the group Planning, which he later left rather quickly.

A. Baes house by architect Maurice Demeester | 1935

Maurice De Meester (° Ghent 1890 / † Bruges 1965) studied at the Ghent Academy and came to live and work in Bruges after working in the Netherlands for a while during WWI. Together with Huib Hoste he brought Dutch brick modernism to Bruges. Well-known works of his are the so-called Gistfabriek and a director’s house in the J&M Sabbestraat. The semi-open house on the Gistelse steenweg is a fine example of the plastic treatment of building volumes. The block windows after the Dutch model – unfortunately the joinery has been mutilated – are always placed at the corners. The central staircase is lit zenitally. This was the house where Marc Dessauvage lived and worked until he moved into his own house in Loppem.

House J. Lem by architect Peter Callebout | 1963

On a narrow strip – the street side is also on the south side of the plot – Peter Callebout built this single-family house with relatively few means. The volume is covered over the entire depth with a pent roof, ending on the striking south facade: no more than a wood structure filled in with windows and plywood panels, so that the sun can penetrate into the deepest corners. One side wall is solid and painted white, the other was finished with planks, unfortunately now replaced. The open plan of the ground floor provides space for the living areas and a sleeping area. Under the sloping roof, there is still room on the street side for a second sleeping corner. Originally, the color choice for the street façade was very contrasting. This unknown gem is one of the many minimalist homes designed by architect Callebout (° London 1916 / † Brussels 1970). He studied at the Bruges academy and was further trained in Bruges by his father Ernest.

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Jacques Pêtre | 1961

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Jacques Pêtre | 1961

Matthias Decleer

House A. Baes | Maurice Demeester | 1935

Matthias Decleer

House A. Baes | Maurice Demeester | 1935

Matthias Decleer

House J. Lem | Peter Callebout | 1963

Matthias Decleer

House J. Lem | Peter Callebout | 1963

Architect house of architect Werner Vandenbogaerde | 1966

The house is located on a corner lot and with its tight volumes it is a real eye-catcher. The studio and living areas are located on the ground floor. The studio is located at the front on Doornstraat, set between two inner gardens that are completely walled. These walls also encompass the garage so that the whole gives the impression of being an elongated closed volume. The living space at the rear also has a spacious courtyard enclosed by walls, which provides privacy compared to the lane at the back of the plot. This creates a play of volumes above which – separated only by columns with a glass strip – the floor appears to float. The house was designed by Werner Vandenbogaerde (° Bruges 1937 / † Bruges 1981), a graduate of the Sint-Lucas Institute in Ghent and permanent employee of architect Crist Vastesaegher (° Tollembeek 1925 / † Bruges 2012), where he worked for many years on numerous churches and schools.

A. Geerardyn house by architect Huib Hoste | 1926

Originally, the house belonged to a printing company behind it. The semi-open house is sculpted with protruding parties, awnings and bay windows. The walls are in brick with the two faces of the facade treated in different shades. The joinery has been preserved, which is extremely rare for a building nearly 100 years old. The furniture in the living room has also been preserved and is on display in the Design Museum in Ghent. The client, Achiel Geerardyn, was a printer and publisher until his business went bust in 1935. His printing house mainly published works on the Flemish struggle, religion, art and also an architectural work Van Wonen en Bouwen written by Huib Hoste. Hoste was sometimes called in to design Geerardyn’s books and designed both the house and the unfortunately disappeared printing house.

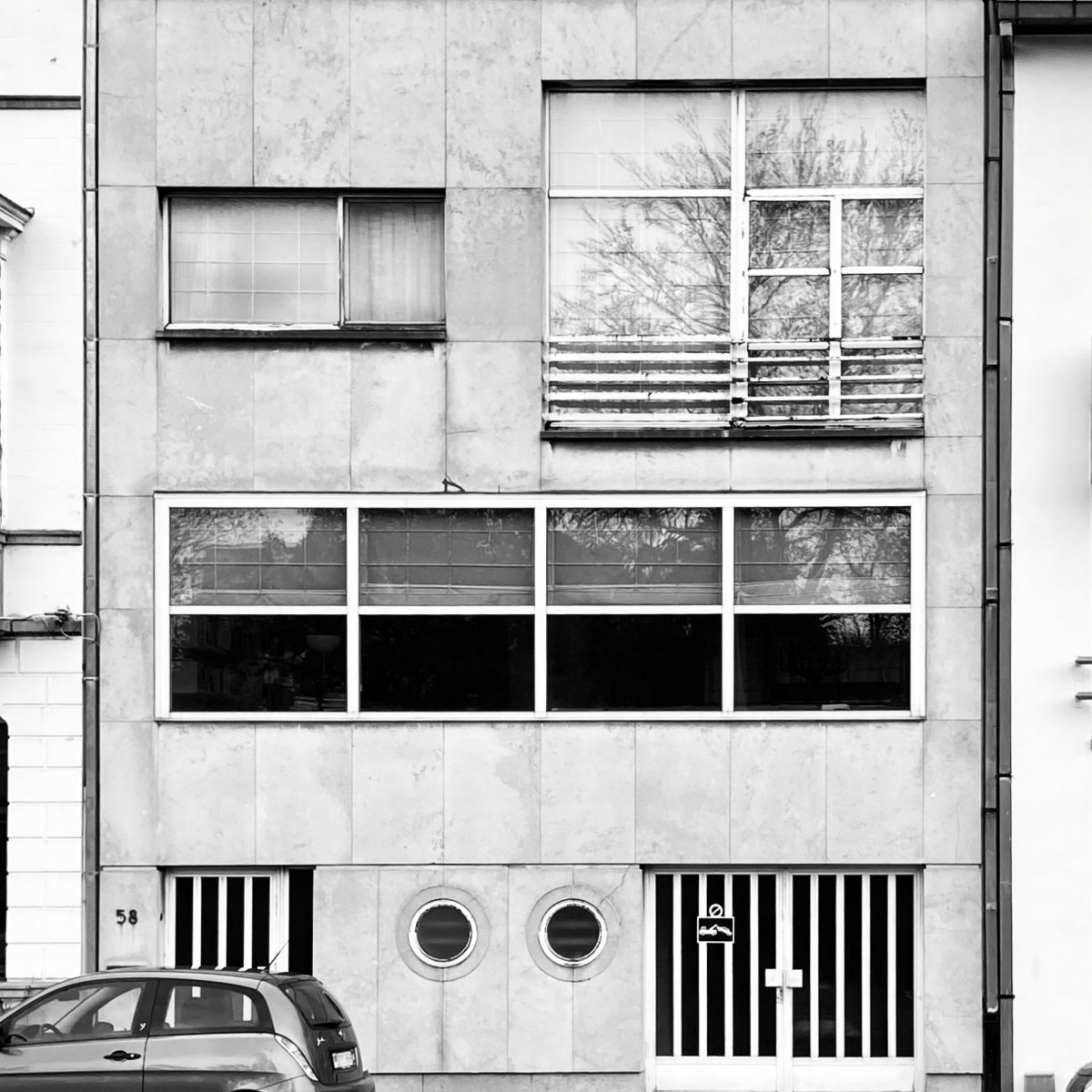

Townhouse B. Broucke by architect Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

There are not that many modernist terraced houses. Axel Ghyssaert also sought here to obtain maximum transparency. The facade is articulated by horizontal, closed bands. The windows in the alternating open strips have been withdrawn in plan. This leaves room to provide planters – a feature that also occurs in other Ghyssaert projects – so that nature is drawn into the home. The great openness is therefore somewhat hidden from view from the street and at the same time shade is provided on this southwest facade. The interior is organized around an open staircase, brightly lit by a large epoxy roof dome. Both the street and the garden are accessible via minimalist slopes, here too with the intention of keeping the boundary outside-inside to a minimum. Ms. Broucke’s practice was planned on the semi-underground floor. Axel Ghyssaert always took the situation and context of the construction site into account. Here too he strictly adhered to strict regulations, both in terms of height and roof shape. What has actually been built in the area shows how relatively those regulations were ultimately applied.

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Werner Vandenbogaerde | 1966

Matthias Decleer

Architect house | Werner Vandenbogaerde | 1966

Matthias Decleer

House A. Geerardyn | Huib Hoste | 1926

Matthias Decleer

House A. Geerardyn | Huib Hoste | 1926

Matthias Decleer

Townhouse B. Broucke | Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

Matthias Decleer

Townhouse B. Broucke | Axel Ghyssaert | 1964

Company and House J. Billiet from architect Huib Hoste | 1928

Just like the Geerardyn house, this house is situated in the post-war period of Huib Hoste, where it is still strongly influenced by Dutch modernism. In 1927 he was commissioned by Jules Billiet, manager of a painting company, to design a diamond polishing shop with a house. The house and company are built on a double plot, with a passage to the company being kept open. The semi-open house is divided into two volumes: one lower with the entrance and one higher for the rest of the house. The cornice of the lower part is the same height as that of the bay window on the first floor, although both are separated by a dominant chimney. Here, too, a pitched roof was mandatory: the choice fell on a hipped roof, so that it is hardly visible from the street. Inside, one can speak of a total concept: furniture and decoration are designed by Hoste. The furniture ended up in private collections, yet 2 cabinets that complete the interior of the living room could be purchased after negotiation. The polychromy of the living room has been preserved under an exact copy so that the concept could still be evoked to a large extent. Huib Hoste (° Bruges 1881 / † Hove 1957) was strongly involved in Catholic, ultramontan neo-Gothic style through his upbringing – certainly under the influence of Canon A. Duclos. After his stay in the Netherlands, he evolved towards modernism, in which he continued to grow in the 1930s and was also present at the first CIAM conference.

Les Heures Claires by architect Georges Van Houtryve | 1936

For Bruges, this is the best example of Art Deco architecture, following the example of the Parisian avant-garde. The architect Georges Van Houtryve (° Bruges 1904 / † Bruges 1961), son of a well-known brewing family, has left a very heterogeneous oeuvre. The clients were the couple J-C de Brouwer and J. de Falloise. He was the son of the famous Bruges industrialist, publisher and art lover; she was the daughter of a prominent Liège family, who gave them this villa as a wedding gift! However, their stay in this villa was short-lived. The semi-open house follows the row of houses in the street. Because the street curves just in front of the house, a spacious esplanade is created. The play of white plastered volumes makes it possible to read the building well. The entrance is prominent with a beautiful Art Deco wrought iron front door – above it was the name of the villa Les Heures Claires, but it has now disappeared. To the left of it are the living areas, to the right the staircase illuminated by a monumental, vertical window, centrally located in a subtly hidden secondary symmetrical plan.

Townhouse H. Breemersch by architect Nachman Kaplansky | 1936

The Huibrecht Breemersch-Catoor couple ordered their townhouse from an Antwerp Jewish architect, without us being able to find out what connection there was between this factory manager and the architect. Although this is probably the only truly modernist house in the center of Bruges (still on the ring road), the concept is very bourgeois, with redundant circulation for staff and owner. The ground floor is completely occupied by a deep garage and service areas. Via a wide elegant staircase you reach the clean floor – as the plans indicate – with the living areas. This central staircase space receives a lot of attention due to its spacious dimensions and zenithal light. A somewhat narrower staircase leads further to the couple’s bedrooms. The house has been built in mirror image with the original permit. The facade is made of Juvigny natural stone with steel frames which, unfortunately, were already replaced in 1968. Even before the Germans invaded our country in 1940, architect Nahman Kaplansky (° 1904 Bielsk Podlaski / † Israel?) Took flight to Tel-Aviv.

Matthias Decleer

Office and house J. Billiet | Huib Hoste | 1928

Matthias Decleer

Office and house J. Billiet | Huib Hoste | 1928

Matthias Decleer

Les Heures Claires | Georges Van Houtryve | 1936

Matthias Decleer

Les Heures Claires | Georges Van Houtryve | 1936

Matthias Decleer

Townhouse H. Breemersch | Nachman Kaplansky | 1936

Matthias Decleer

Townhouse H. Breemersch | Nachman Kaplansky | 1936