2016

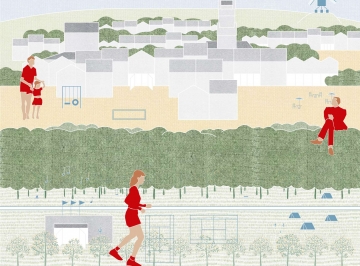

Living

By 2030, 330,000 additional families must be housed. New homes will have to be built for some of them. How can these homes contribute to a better spatial policy in Flanders, which counteracts further suburbanization and fragmentation of the residential area? How can we achieve attractive and affordable living environments in a socially integrated way? How can we accommodate individual housing requirements with less social burden and costs? With which housing projects can we actually achieve a break in the trend in Flemish housing production?”

Within the current discourse on possible solutions for various, acute housing problems in Flanders, new, collective housing forms are often put forward. The increasing population, changing family structures and the decreasing amount of free space are forcing our generation to be more creative with living and designing. The fixed values and traditions that have long served as an excuse for the so-called brick in the stomachs of all Belgians have long ceased to correspond to the needs of the acute social housing problem. We need to redefine the traditional housing model and develop new, more sustainable housing models.

Flanders remains the most fragmented and parceled out region in Europe. The space taken up by hard functions such as housing, industry, intensive agriculture, roads and mobility is significant. Despite the limited surface area and a high population density, we are by no means sparing with space. Buildings in Flanders are very scattered, without a clear pattern. We are still building or hardening 7.5 ha (or 15 football fields) every day at the expense of the open space.

After Monaco and the Vatican City, Flanders has the largest paved surface per square meter in the world and the densest road network in Europe. If Flanders continues to occupy open space at the same rate, according to a study by the KULeuven, more than 40% of the available space will be built up by 2050.2 The urban flight of the previous decades has ensured that housing mainly takes place in large allotments in outdoor areas, in scattered and ribbon development, with low density. As a result, there are too many traffic-generating functions such as retail warehouses, shopping centers, business parks. Nature areas are being cut up and are too small and too fragmented, causing them to lose vulnerable animal and plant species. Flanders is one of the least forested areas in Europe, yet a lot of forest is still being cut down. If we do nothing and Flanders continues to occupy open space at this rate, the Flemish diamond will be almost completely built up by 2050. The current situation must be brought to a halt! How can we strive for a good living environment? How can affordable and good living be realized? After all, quality housing is the expression of the functioning of a society, of the functioning of a policy. Current housing concepts are outdated. Traditional living is challenged by innovative housing typologies. Not only should the housing form be rethought, we should also look for new forms of collective commissioning and other visions on land use. Societal challenges such as land scarcity, affordability, environmental protection, mobility, aging and family dilution are inextricably linked to this.